Clach Mhicleoid, Harris

Stones

of Wonder

QUICK LINKS ...

HOME PAGE

INTRODUCTION

WATCHING

THE SUN, MOON AND STARS

THE

MONUMENTS

THE

PEOPLE AND THE SKY

BACKGROUND

ARCHAEOASTRONOMY

USING

THE SITE DESCRIPTION PAGES

VISITING

THE SITES

THE

LEY LINE MYSTERY

THE

SITES

ARGYLL

AND ARRAN

MID

AND SOUTH SCOTLAND

NORTH

AND NORTH-EAST SCOTLAND

WESTERN

ISLES AND MULL

Data

DATES

OF EQUINOXES AND SOLSTICES, 1997 to 2030 AD

DATES

OF MIDSUMMER AND MIDWINTER FULL MOONS, 1997 to 2030 AD

POSTSCRIPT

Individual

Site References

Bibliography

Links

to other relevant pages

Contact

me at : rpollock456@gmail.com

Standing Stone NG041973*

How to find: Follow the A859 road south from Tarbert for 18km, travelling through what must surely be the rockiest landscape in Scotland, until you reach Horgabost. After passing a small promontory a roadside sign indicates the stone, which is visible from the parking place, on a low hill beyond the far end of the beach.

Best time of year to visit: Equinoxes, about March 20th and September 22nd.

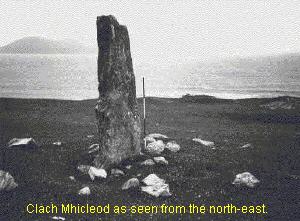

This

is an impressive and dramatically situated stone, on a grassy slope above

a perfect and usually empty Hebridean beach. It is a tall stone, over

three metres high, with the packing stones at the base visible; it is

150cm wide but only 40cm thick, and so presents two flat faces which draw

the eye out over the sea.

This

is an impressive and dramatically situated stone, on a grassy slope above

a perfect and usually empty Hebridean beach. It is a tall stone, over

three metres high, with the packing stones at the base visible; it is

150cm wide but only 40cm thick, and so presents two flat faces which draw

the eye out over the sea.

This stone is also a good example of the debate about the evidence which the stones present. Alexander Thom interpreted Clach Mhicleoid as the backsight for the line to the distant islands of the St. Kilda group, fully 90km out in the ocean, the tops of which can be seen in clear weather.1 The bearing to the most northerly and highest island of the St Kilda group, Boreray, is 271° and gives a declination of 0°, that of the setting sun at the equinoxes, when day and night are of equal length.

This interpretation of the stone as a prehistoric astronomical marker may be correct, as stones from a later period erected on shorelines to be seen from the sea usually have their wide face turned seawards, whereas Clach Mhicleoid is at right angles to the sea.

However,

a survey of the stone's indicated bearings on the horizon gives a value

of 275° for the left-hand side and 282.5° for the right. The stone

leans to the south, and if it were originally vertical would have indicated

an azimuth of about 290.5°. None of these azimuths produces a significant

declination value.

However,

a survey of the stone's indicated bearings on the horizon gives a value

of 275° for the left-hand side and 282.5° for the right. The stone

leans to the south, and if it were originally vertical would have indicated

an azimuth of about 290.5°. None of these azimuths produces a significant

declination value.

So the stone doesn't actually point towards Boreray. Even with the better weather in the Neolithic and Early Bronze age period, the number of days of the year when the island of Boreray could be seen at all must have been very limited.

Whether you would accept the stone

as simply indicating the place to stand and an approximate indication

of the direction in which to look, or whether you believe some more definite

indication is required before such a line could be accepted is a personal

choice. But a visit to this part of the Hebrides is an experience not

to be missed.