The Legacy

Stones

of Wonder

QUICK LINKS ...

HOME PAGE

INTRODUCTION

WATCHING

THE SUN, MOON AND STARS

THE

MONUMENTS

THE

PEOPLE AND THE SKY

BACKGROUND

ARCHAEOASTRONOMY

USING

THE SITE DESCRIPTION PAGES

VISITING

THE SITES

THE

LEY LINE MYSTERY

THE

SITES

ARGYLL

AND ARRAN

MID

AND SOUTH SCOTLAND

NORTH

AND NORTH-EAST SCOTLAND

WESTERN

ISLES AND MULL

Data

DATES

OF EQUINOXES AND SOLSTICES, 1997 to 2030 AD

DATES

OF MIDSUMMER AND MIDWINTER FULL MOONS, 1997 to 2030 AD

POSTSCRIPT

Individual

Site References

Bibliography

Links

to other relevant pages

Contact

me at : rpollock456@gmail.com

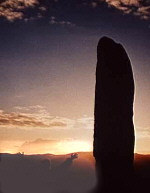

You are standing with friends and family on a wide hill above the village. It is night, and you shiver in your clothes of animal skin and wool. Your feet are bare. The ground is cold, for it is winter. Most of the trees on the hilltop are gone, only the stumps at waist height remaining. You know this, for you cleared many of them with the axe yourself. Looking down there is nothing to be seen of the land, it is blanketted by the dark. Even the village is invisible, though you can smell the smoke from the wood fires inside the houses drifting up the slope in the southerly wind.

The only sounds are from the water falling through the glen below, and the old trees of the far forest margin creaking in their upper branches as the breeze touches them.As you lift your head a pale light defines the shape of the forested mountains around, each individually known ; to the west the flat and black line of the ocean is clear against the sky. The crescent moon is young, and set into that sea before you rose from your bed of heather and furs and came with your people to the hill. So only the stars are in view, shining in their colours in the cold air. You see the eternal patterns, pure and distant, where the gods make their home, and you feel glad. Glad to be able to see, and glad to be alive for the morning.A stir among the small group beside you. A glow of grey and yellow has come to the low part of the horizon. It is reflected in the eyes of those who watch for the dawn to come. Even as you notice it, the fainter stars in the east fade away as colour comes slowly to the sky again. When will the old one move ? Not yet. You feel faint and empty, breathing the cold air.

Balanced on the edge of the new time,

you are part of the land, waiting with it for the touch of warmth.How

long now ? No-one moves. A ruddy light now in the east, with a deep grey-blue

around and above. You can see your breath, and the dew on the hair of

your companions. The cold sinks onto you, your neck and shoulders are

numb, you feel ice beneath your feet.And

now the old one strides off, you have all done enough. Along through the

grass to the crest, and down in a sweeping line you go, the old one leading.

Down the steep side of the hill, moving fast. Through the stream you run,

and up the far bank, then along the dyke. A dog is barking in the village

as the others come out of the houses in the grey light. They hurry to

join with you, and all go through the rough gate to the flat field, where

stand the stones. Your father

and mother helped to put the stones up. Helped to quarry them, helped

to make the ropes to drag them with, cut the rollers, dug the holes, pulled

on the levers, turned and packed them in their sockets and watched them unchanging through the seasons. Your parents

are gone. But they wanted the stones to stand in line for ever.The

old one gathers all the people, sets them in a group on the north side

of the stones. The young children are shivering, surprised by the early

arousal, arms around their brothers and sisters. You see how the sky glows

in the south-east, and a pale blue icy light has touched the whole sky.

The hilly horizon behind the stone is black and sharp against the light,

painful to see, but everyone watches.Everything

important and of value is around you. The village, the fields, the animals,

the grain. The tools, the axes and the bows. The old one, the people of

the village, the children. The stones, standing to mark the day. And life.

All you need is the promise of the end of the dark winter, the light,

the warmth, the gift of the season for all things to grow.And

the promise comes. A brilliant flare on the horizon directly behind the

stones, and then the disc of the sun itself, gloriously bright, rises

fast up and across the horizon, as your people shout and stamp and the

old one murmers the prayer of thanks. The shortest day is upon you, the

day the stones record. But after today is the promise that winter will

die, the nights will grow shorter and the sun grow warmer, the grass for

the cattle will grow long and green, the earth will be warm for the grain

to grow and the harvest to ripen. On this day the sun turns in its course

and so life itself can continue in its eternal renewal. You have seen

the night, the dawn, and the new day. You are glad, and with the rest

you move forward to touch the stones, your eternal friends, in thanks.

sockets and watched them unchanging through the seasons. Your parents

are gone. But they wanted the stones to stand in line for ever.The

old one gathers all the people, sets them in a group on the north side

of the stones. The young children are shivering, surprised by the early

arousal, arms around their brothers and sisters. You see how the sky glows

in the south-east, and a pale blue icy light has touched the whole sky.

The hilly horizon behind the stone is black and sharp against the light,

painful to see, but everyone watches.Everything

important and of value is around you. The village, the fields, the animals,

the grain. The tools, the axes and the bows. The old one, the people of

the village, the children. The stones, standing to mark the day. And life.

All you need is the promise of the end of the dark winter, the light,

the warmth, the gift of the season for all things to grow.And

the promise comes. A brilliant flare on the horizon directly behind the

stones, and then the disc of the sun itself, gloriously bright, rises

fast up and across the horizon, as your people shout and stamp and the

old one murmers the prayer of thanks. The shortest day is upon you, the

day the stones record. But after today is the promise that winter will

die, the nights will grow shorter and the sun grow warmer, the grass for

the cattle will grow long and green, the earth will be warm for the grain

to grow and the harvest to ripen. On this day the sun turns in its course

and so life itself can continue in its eternal renewal. You have seen

the night, the dawn, and the new day. You are glad, and with the rest

you move forward to touch the stones, your eternal friends, in thanks.

Midwinter, the time of the winter solstice when the days are shortest,

was the time of one of the main festivals of the year for the peoples

of pagan prehistoric Europe. The

significance of such times of year (and of the seasonal festivities which

accompanied them) is difficult for the modern mind to appreciate. But

the importance of the midwinter celebrations can be gauged by the fact

that a version of those celebrations is still with us today. When the

Christian church settled on the dates for its own festivals, it placed

one of the most important at midwinter, within a few days of the winter

solstice, to encompass and absorb the pagan rites.Another

important feast day, that of St John the Baptist, was set close to midsummer,

when the days are longest and the sun is at its highest position in the

sky. There are many other connections between our modern festivals and

calendrical system, and ancient skywatching. Three of our days of the

week are named after heavenly bodies.

The date of Easter, the most important Christian festival, is set today, as in the past, as the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox. This is why the date of Easter varies - it is not simply a position in the modern calendar, it is determined by the moon. The months of our calendar are also derived originally from the natural cycle of the moon in the sky, from full to waning crescent to new to waxing crescent and so to full again, a period of about 29 days.Another interesting connection concerns the Scottish quarter days of Lammas (early August), Martinmas (early November), Canlemas or Candlemas (early February) and Whitsun (originally early May). These quarter days, also known as 'term days', were when rent was due, leases were signed, and contracts for farm labour began and ended. These were the periods when families would move house, and fairs would be held. These four days are the equivalent of the old Celtic festivals of Lunasda, Samhuinn, Imbolg and Bealtuinn which were at the same times of the year, being the four half way points between the solstices and equinoxes. Bealtuinn and Samhuinn seemed to be the most important times, Samhuinn being the period in spring when the cattle were taken to the hills, and Samhuinn the time when they were brought down again before the onset of winter [McNeill 1956, page 9. See also McNeill, 1959, page 55. It is noted here that Beltane fires were lit all over the Highlands until the middle of the 19th century.].

The modern activitities at Hallowe'en and Bonfire night have a direct connection with the ancient festival of Samhuinn and they have managed to retain some of its pagan and elemental character.It is easy to forget today that the calendar we use, and the way we segment time, are both ultimately derived from the movements of the heavenly bodies. The technology that supports and cossets us in centrally heated homes and air conditioned offices and bright shopping malls, and puts digital watches on our wrists has inevitably distanced us from the natural rhythms of the sky and the earth. The sun, in its rising and setting and its height in the sky was once the most important object in the lives of our ancestors - the source of light, heat and growth, the creator of the seasons and of the year. It is now what we hope to see for two weeks on our summer vacation, usually in a more southerly resort. The moon, once univerally used as a measure of time, its position and phase the common currency of everyone, provider of the only light which allowed night-time travel, has now become merely an object of surprised notice on a drive home. The last of those who took off their hat or touched a silver coin as a mark of respect on their first sight of the full moon every month have passed away into history.

This Web guidebook is intended to

restore an informed interest in the sky. Its subject is the megalithic

remains of Scotland, erected in the Stone age and Bronze age about 6,000

to 3,500 years ago. Many of these structures mark the rising and setting

points of the sun, for different times of the year, and the moon, at certain

points in its long cycle. These standing stones, stone circles and chambered

cairns are the most enduring monuments left by these prehistoric inhabitants

of Scotland, and over the last hundred years many workers from different

disciplines have investigated the astronomical alignments which these

sites incorporate. But a lot of the published research and survey work

is not easily accessible, and none of it relates to Scotland alone. This

Web guidebook will serve as a guide to some of the best known, most easily

visted or most interesting prehistoric sites in Scotland which have orientations

to the sun, moon and stars. It is not intended to be comprehensive, and

there are hundreds more sites which you may discover for yourself, which

indicate significant solar or lunar events.