Callanish / Calanais Standing Stones, Lewis

Stones

of Wonder

QUICK LINKS ...

HOME PAGE

INTRODUCTION

WATCHING

THE SUN, MOON AND STARS

THE

MONUMENTS

THE

PEOPLE AND THE SKY

BACKGROUND

ARCHAEOASTRONOMY

USING

THE SITE DESCRIPTION PAGES

VISITING

THE SITES

THE

LEY LINE MYSTERY

THE

SITES

ARGYLL

AND ARRAN

MID

AND SOUTH SCOTLAND

NORTH

AND NORTH-EAST SCOTLAND

WESTERN

ISLES AND MULL

Data

DATES

OF EQUINOXES AND SOLSTICES, 1997 to 2030 AD

DATES

OF MIDSUMMER AND MIDWINTER FULL MOONS, 1997 to 2030 AD

POSTSCRIPT

Individual

Site References

Bibliography

Links

to other relevant pages

Contact

me at : rpollock456@gmail.com

Standing Stones, Circle, Cairn NB213330*

How to find: The stones are in the village of Callanish / Calanais on the west coast of Lewis, and are signposted off the A858. The site is in state care.

Calanais location map is here.

Best time of year to visit: Equinox sunsets ; lunar major standstill ; any clear night.

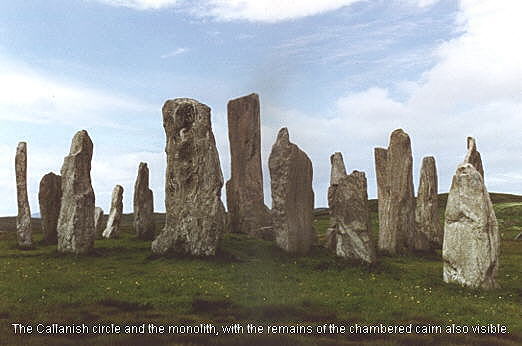

This is a wonderful and awe-inspiring stone monument, undoubtedly the most famous prehistoric site in Scotland. It stands on a rise and is visible from a wide area around, paticularly when picked out by the shifting rays of sunlight through the broken cloud of a Lewis summer sky. Visitor numbers are now such that a path has been laid around the perimeter of the site by Historic Scotland to lessen the damage to the interior of the avenue and circle.

Callanish has now become a focus again for visits at the summer solstice, by those perhaps hoping to see the 'shining one' who according to local legend walks up the avenue on the midsummer dawn. These visits are the continuation of a Lewis tradition (carried on in spite of the church's opposition) which also saw the stones attended on May day.

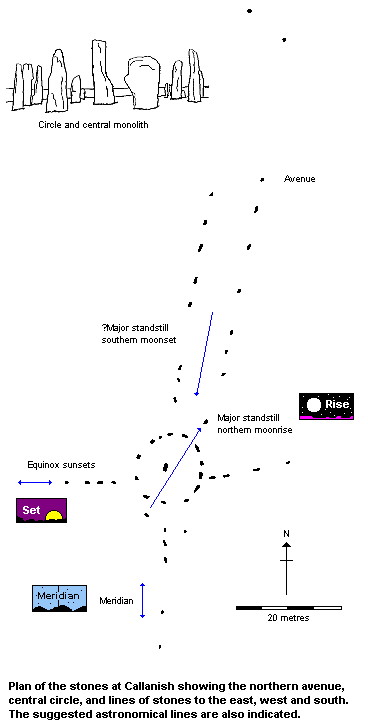

The stones, of Lewisian gneiss, were buried in peat up to about the height of an adult before they were cleared in the year 1857. There are several elements to the site. A ring of large stones about 12 metres in diameter encloses a huge monolith at its centre. Also in the middle of the ring are the remains of a chambered cairn, revealed when the peat was cut away. As the cairn appears to have been added to the circle, and chambered cairns are considered to be Neolithic in date, it seems clear that the site in general is also Neolithic. (Standing stones and stone circles elsewhere are often stated to be Bronze age, but without dating or stratigraphical evidence. Some are just as likely to be of stone age date).

Running north from the stone circle are two parallel lines of stones forming an avenue about 80 metres long. There are now 19 stones in the avenue. Any visitor entering the site from the north will feel impelled to walk up this avenue to the circle, although this is now discouraged.

Also running from the circle are single

lines of stones to the east (4 stones), west (4) and south (6). In plan,

the site has the form of a cross.

Much work has been done over the last 80 years on the astronomical orientations built in to the monument at Callanish, some of which are still controversial. Boyle Somerville suggested in 1913 that the northern avenue was positioned to indicate the rising of the star Capella about 1800BC¹. He pointed out that the west row indicates the setting sun at the two equinoxes. He also suggested that a line between the two stones outside the circle (to the north-east and south-west) indicated the moon rising at its maximum (major standstill). This was the first time a surveyor introduced evidence for a lunar line for any prehistoric site in Scotland.

More recently researchers have suggested that the avenue should be viewed as pointing south, to the position of the setting southern moon at the major standstill², though the horizon is blocked by the rocky knoll to the south of the site. The southern line of stones together with the large monolith in the centre of the circle has a bearing of 180.1°, and is an accurate indicator of the meridian, true north-south³. There are other many examples of meridional stones in this guide. Such a line indicates to the north the 'pole' around which the stars of the night sky appear to revolve, and to the south the highest position the sun and moon attain in the sky on any day.

All, or only some of these lines may have been deliberately intended by the builders. But there are no good orientations to the sun at Beltane (May day) or midsummer. So the traditional visits at these times of year must have a later origin and suggest again the limited value of the surviving folklore attached to prehistoric sites and remind us of the huge span of time which separates us from our stone age forebears.

Update:

Steven Whitehead has created a site exploring the east-west lines, and he plausibly suggests that the east row is an indicator of the rising full moon closest to the autumnal equinox. Explore Steven's page 'Calanais I (Callanish) and the Equinoctial Moon' here.