Ballinaby, Islay

Stones

of Wonder

QUICK LINKS ...

HOME PAGE

INTRODUCTION

WATCHING

THE SUN, MOON AND STARS

THE

MONUMENTS

THE

PEOPLE AND THE SKY

BACKGROUND

ARCHAEOASTRONOMY

USING

THE SITE DESCRIPTION PAGES

VISITING

THE SITES

THE

LEY LINE MYSTERY

THE

SITES

ARGYLL

AND ARRAN

MID

AND SOUTH SCOTLAND

NORTH

AND NORTH-EAST SCOTLAND

WESTERN

ISLES AND MULL

Data

DATES

OF EQUINOXES AND SOLSTICES, 1997 to 2030 AD

DATES

OF MIDSUMMER AND MIDWINTER FULL MOONS, 1997 to 2030 AD

POSTSCRIPT

Individual

Site References

Bibliography

Links

to other relevant pages

Contact

me at : rpollock456@gmail.com

Standing Stones NR220672*

How to find : From Bridgend take the A847 west. After 7km take the B8018 and follow it north for 5km, then turn left on the minor road along the north side of Loch Gorm. Ballinaby farm is 2km along this minor road. The stones are in the field to the north-west of the farm.

Best time of year to visit : Lunar major standstill (see dates).

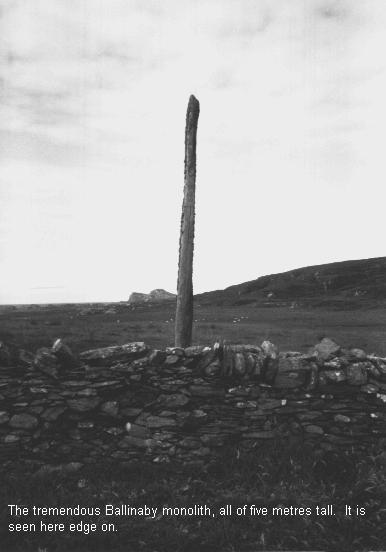

At Ballinaby you will find a magnificent slab over 5 metres tall, with the face of the stone about a metre wide, and the thickness only 30cm (stone A). This stone is standing by a modern dyke. About 200 metres away to the north-east is another stone two metres tall (stone B), which is the remaining part of an originally much taller stone. It was probably deliberately broken. An eighteenth century report mentions three 'stupendous' stones standing in a row here - the third stone has now completely disappeared. Its fragmented remains are probably within the dyke.

Anyone visiting the site will notice at once that the flat face of the stone is aligned towards a distinctive and unusually shaped coastal promontory in the north-west. This is about 2km distant. The moon sets over this promontory at its extreme northerly position during the major standstill (declination about +28°).

Also of interest is the original row of stones itself, of which the large 5m stone A and the smaller 2m stump B remain to give the line. Looking from A to B one sees the nearby hill creating a horizon well above the smaller stone, and the azimuth of 25° gives a declination of nearly 35°, which is of no known celestial interest.

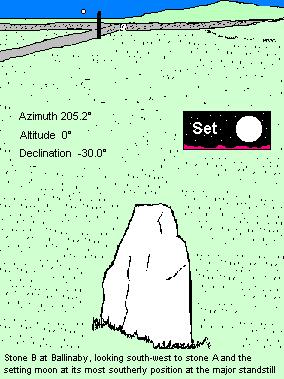

However, standing by B and looking towards A, the line has an azimuth of 205.2°, which with a horizon of about 0° gives a declination of -30.0°, the setting position of the moon at its extreme southerly point during the major standstill. This can hardly be a concidence, and it may be that having erected the large thin slab to mark the most northerly setting line of the moon the builders then set up the line of stones to record the southernmost position of the setting moon on the horizon.

This could have been done by watching the full monthly cycle of the moons about the time of the summer solstice and then again at the time of the winter solstice. At midsummer, the very first crescent of the moon before the solstice would be close to the most northerly position of the moon (about +28°). After about two weeks the full moon close to the solstice would then have moved south, to rise and set quickly on the southern horizon (-30°). At midwinter, on the other hand, the first crescent of the moon at the solstice would be at the southerly extreme (-30°), with the full moon closest to the solstice itself rising and setting on the northern horizon at about +28°.

We are unlikely ever to know the motivation of the prehistoric peoples who erected these astronomical markers, but we could speculate that there were festivities and rituals at both summer and winter solstices ; the complement of the low full moon to the high sun at midsummer, and the high full moon to the low sun at midwinter must have been a significant and obvious natural wonder - which we can now rediscover.

Stone A at Ballinaby, with stone B visible in the middle distance. The ranging pole is in 50cm divisions.